It is capitalism's fault that the U.S. lost the war in Vietnam. War planners were convinced that superior production capacity - the ability to make weaponry and kill the enemy - made anything but victory in Vietnam unthinkable. They were wrong!

Just like a factory cranking out sedans in Dearborn, Michigan the war in Vietnam became a production system of rational, scientific warfare. Members of the general staff were more than happy to apply the analogy. Lieutenant General Julian J. Ewell visualized the battlefield as an assembly line saying, “once one decided to apply maximum force, the problem became a technical one of doing it efficiently with the resources available.” Like an assembly line there were debits and credits. On the debit side were US troops killed or wounded in action, accidents, and courts martial combined with capital losses - aircraft shot down, destroyed artillery pieces, bases blown up. On the credit side were troop reenlistments, prisoners of war captured, and above all enemy body counts.

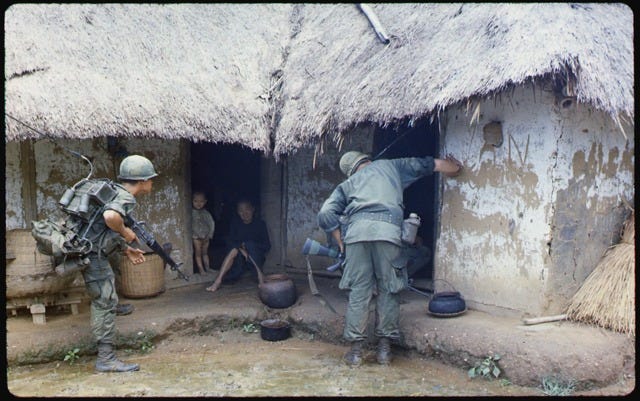

Also like factory work, there was labor and there was management. The labor force was made up of GIs, military brass were the managers. But Vietnam wasn’t actually fought rifle against rifle in the jungle. The main way American ground forces were used by war managers was as bait. The American military machine was huge and loud. The enemy always knew where American units were and would wait to fight until they felt they had the advantage. A platoon of Americans would go humping through the bush attempting to draw the Vietcong into a firefight. The task of American ground troops was to mark the spot with smoke grenades and withdraw so that planes could launch a napalm attack. This strategy engendered a lot of animosity amongst the American labor force against war managers. Upper management didn’t seem to care much if American boys died because the production goal was maximum enemy body count. By drawing the enemy out into the open and launching bombing runs it was possible to kill much more efficiently and increase production capacity.

In his book The Perfect War, Technowar in Vietnam, the basis for much of these posts, author William James Gibson says that this focus on kill ratios and production gave Vietnam a veneer of rationality, providing the appearance of a lawful war - not a bloodbath. But the relentless focus on productivity is precisely what turned Vietnam into a bloodbath. Body counts were the primary measurement for separating productive units from unproductive ones. Ranking officers set “production quotas” and there was intense pressure to meet them. Showing the brass high body counts was crucial for low-ranking officers to earn promotions in a highly competitive environment. Not meeting quotas was tantamount to disloyalty.

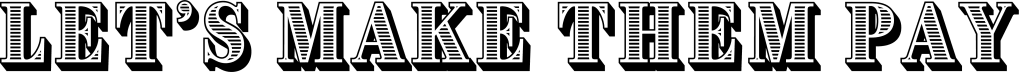

Measuring body counts could sometimes be problematic, however. In the far northern provinces troops in the People’s Army of Vietnam, or NVA, wore uniforms. In the rest of the country things weren’t always so clear cut. Unless they were shooting at you it could be near-impossible to tell hostile enemy soldiers from civilians when the smoke cleared and it was time to start counting bodies. The iconic “black pajamas” that Vietcong wear in the movies were pretty much what every Vietnamese peasant wore, so clothing was no dead giveaway. Some Vietnamese were considered the enemy if they took “evasive action” after American troops opened fire on them. Some American units added a corpse to the enemy body count after looking at their hands: more calluses meant an innocent farmer, fewer calluses mean Vietcong. Other units looked at a corpse’s ankles: If they were scratched up that meant they had been running through the jungle and were Vietcong. Sometimes the determination was geographic. Any person found in areas declared “free-fire zones” was considered the enemy. According to Gibson, General William Westmoreland declared (apparently with a straight face) that no civilian deaths had occurred in free-fire zones in 1969 – because, remember, any person killed in a free fire zone was ipso facto the enemy.

The demand for bodies created perverse incentives that did more harm than good. On a “search-and-destroy” mission an American unit would move into a village where Vietcong were rumored to be hiding. The village would be evacuated, swept for hidden weapons caches, then burned to the ground – as was done in the infamous Mai Lai incident - “standard operating procedure was to destroy everything and everyone.” [Emphasis in original] Dead bodies were more valuable than prisoners. Gibson quotes veteran Charles Locke who remembered a company captain saying “He didn’t want to hear about any prisoners. He wanted a body count. He said he needed seven more bodies before he could get his promotion to major.” Old men, women, and even children were sometimes counted as enemies killed in action. It’s important to understand that killing civilians was consistent with this overall war production strategy and not an aberration. Yet even as troops were participating in atrocities they recognized how counter-productive search-and-destroy tactics were for the overall war effort. Vietnamese survivors were a threat because they could describe what had happened in their villages. Just as we have seen with drone warfare, survivors were more likely to join the Vietcong or help recruit more peasants for the enemy. Some soldiers perceived killing civilians as the only way to slow the increasing the strength of the Vietcong.

Relentless focus on body counts created an intense pressure inflate numbers that trickled all the way down to grunt-level. Huge enemy body counts were invented out of thin air. According to one soldier: “I know one unit that lost 18 men killed in an ambush and reported 131 enemy body count. I was on the ground at the tail end of the battle and I saw five enemy bodies. I doubt if there were any more.” It was common for Vietcong to drag fallen comrades from the battlefield, the same as American troops. Enemy troops and civilians alike buried their dead. When American soldiers found Vietnamese graves, they were frequently added to the body count – sometimes twice. For some reason capturing an enemy weapon was counted as five bodies: “In other words, if you shoot a guy who’s got a gun and you get that gun, you’ve shot six people.” The enemy body count numbers were inflated in the field and those statistics were then pumped up at pretty much every intervening level of command on their way to the top.

Stunningly, even though everyone at every level of the American war effort knew that the data being fed to war managers was inflated, body count numbers were still treated with complete credulity. By late 1967 the data indicated that victory was at hand. According to the algebraic equations that military planners were using X=enemy soldiers, minus Y=monthly enemy casualty rates it was impossible for North Vietnam to sustain its war against the US. The US military was killing Vietcong soldiers at a high enough rate that they were doubtlessly on the verge of submission. Instead the Tet Offensive happened in 1968 proving that the enemy was in much better shape than the US military thought.

This is part 2 of a 4 part series on how capitalism lost the Vietnam War. In my next post we'll take a look at Vietnam's long history of fighting foreign invaders, Ho Chi Minh's love for America's Declaration of Independence, and why war planners had no idea what they were getting themselves into.

Let’s make them pay.

Assembly Line of Death