Why did the U.S. lose the war in Vietnam? Turns out it was capitalism’s fault. US war planners, hot off victory in World War II were convinced that all it took to win a war was to crank out more tanks, bombs, and planes than the enemy. Turns out they were wrong. Let’s take a closer look at how capitalist war production theories lost the war in Vietnam.

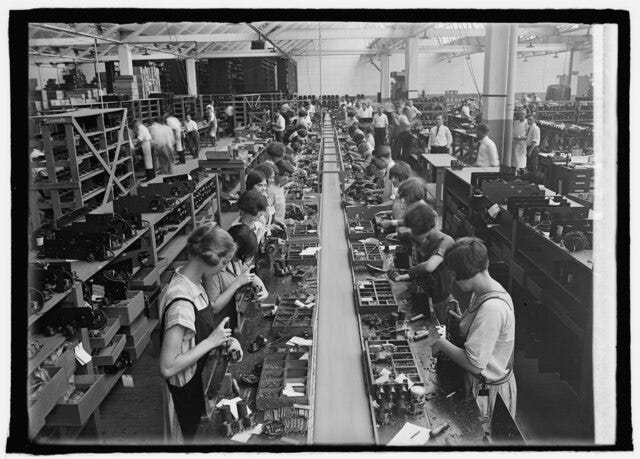

Back on May 9th I did a post about Fredrick Winslow Taylor, the father of scientific management. One of the world’s first business bestsellers was also the most influential, Taylors’s The Principles of Scientific Management. Taylor was trained as an engineer and became a top foreman at Bethlehem Steel company in the early 20th century. The way he saw it every factory worker “plans to do as little as he safely can.” What Taylor called “soldiering” you and I might call “loafing.” Where workers were trying to do the least amount of work spread over the longest period of time Taylor hoped to somehow flip that equation and get workers to do the most work in the least amount of time. Increased productivity was the goal. Taylor would prowl factory floors with a stopwatch and notepad in hand, scrupulously trying to break down manual tasks into a discrete series of measurable moves known as “piece work.” After the parameters for each individual’s productivity were measured managers could set higher and higher output targets.

Taylor was trying to prove “the best management is a true science, resting upon clearly defined laws.” Workers suspected that Taylor was secretly trying to make every employee interchangeable: Say worker Ralph calls out sick – simply spend two minutes teaching Charlie what Ralph does and boom – you don’t need Ralph anymore. Factory workers found Taylorism dehumanizing. The constant repetition of the same movements turned them into unthinking automatons and as workers had feared it did indeed make them easier to replace. Taylorism also greatly weakened the power of unions over time. Part of union strength lay in the knowledge workers gained from years on the job. This institutional memory made it harder to simply swap out a striking workforce with scabs. After decades of Taylorism there was less and less specialization in factory work fewer and fewer irreplaceable employees.

But ultimately American productivity did surge thanks to Frederick Taylor. Scientific management also got part of the credit for helping win World War II. It is said that superior technology and production led the Allies to victory over the Axis powers. The US was able to out-produce Germany and Japan when it came to tanks, planes, and ammunition. It was their war machines versus ours and they simply could not compete. It was only a matter of time until America’s superior war production system wore the enemy down and forced their submission. At then end of the war, American industrial output is a big reason the US made up 50 percent of world GDP.

As scientific management had been applied to industry in the past, some of the big brains in America saw how the rationalization of war production could reshape global power. In 1974 Henry Kissinger reflected on the postwar era saying “A scientific revolution has, for all practical purposes, removed technical limits from the exercise of power in foreign policy.” The way he saw it, since the US had the biggest, most efficient economy and industry capable of making the most technologically advanced war machines on earth, the US possessed almost unlimited power for global control.

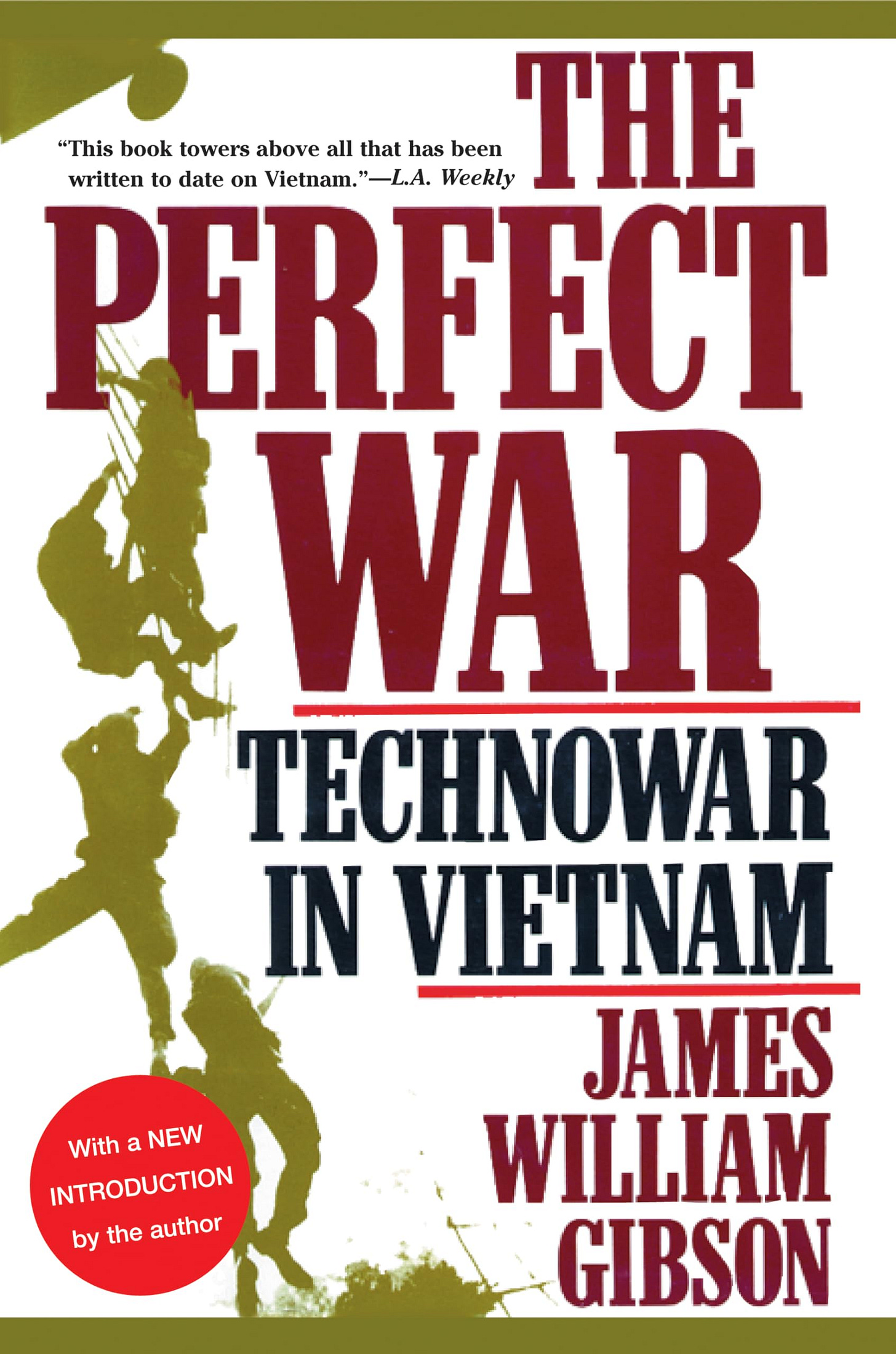

In one of the best books I’ve ever read, The Perfect War: Technowar in Vietnam, author James William Gibson describes how war production theories were applied in Vietnam – a process he calls “technowar.” If there was one man more responsible than any other for bringing scientific rationalization to warfare it was Robert McNamara. As a professor at Harvard Business School during World War II, McNamara first gained fame for organizing bombing raid patterns over Germany. In the 1950s McNamara was vice president and general manager of the Ford Motor Company, one of the “whiz kids” hired by Henry Ford II to use modern planning and scientific management to whip the company’s chaotic organization back into shape after the war. McNamara did such a fine job he was the first person from outside the Ford family to be given the top executive position in 1960. One month later John F. Kennedy named him Secretary of Defense.

As Kennedy’s and then Lyndon Johnson’s Defense Secretary, McNamara approached the war in Vietnam the same way he did when he was making Ford Falcons. Warfare was simply another production equation where one had to find the ideal point on a marginal utility curve. Victory was conceptualized as killing North Vietnamese at a faster rate than they could replenish. Death was the product and whoever had the most efficient production capacity would come out on top. In a war of attrition, the thinking went, the only thing that matters is the technological production system. The United States had Bell helicopter factories cranking out Huey Hogs, Republic Aviation was pumping out F-105 Thunderchief fighter bombers, McDonnell Douglas was chugging out F-4 Phantoms, Boeing assembling B-52 Stratofortresses by the dozens and on and on. The United States was also producing vast amounts of ordinance.

Fun fact: During World War II the US dropped a combined 2 million tons of bombs in the European and Pacific theaters. Between 1965 and 1973 the US dropped at least 8 million tons of bombs on Southeast Asia (not just Vietnam, but Cambodia and Laos too).

Quantitatively there was just no way the North Vietnamese could compete. How could a nation of peasants riding bicycles possibly beat the mighty US war machine? The US had the richest, largest, most technologically advanced economy on earth. Defeat was not only incomprehensible, it was unthinkable. Inconceivable!!!

This is part one of a four part series on how capitalism lost the Vietnam War. In my next post we’ll take a closer look at how the wheels started coming off.

Until then, let’s make them pay.

Share this post