Dear readers, TikTok has a great feature that allows you to repost videos from last year “on this day.” I am especially proud of this series from last year so I thought I would share it here as well. I hope you enjoy…

Free-Market economics is a false religion... which of course implies it's not quite science. In fact, economics has a serious case of physics envy.

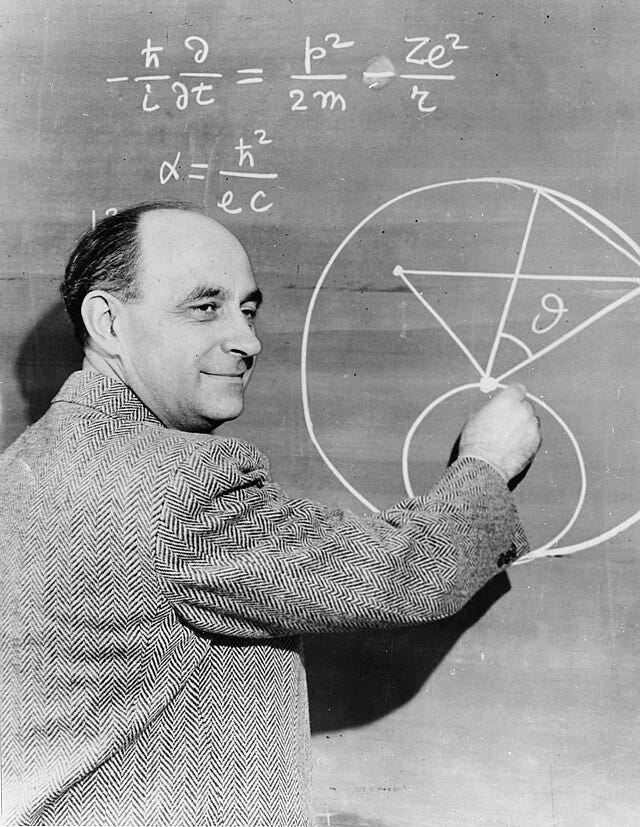

December 2, 1942… almost one full year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the scientific community in the US was in a state of high anxiety. Physicists were sure that Hitler’s war machine, which had a two-year head start, was well on its way to developing a nuclear weapon. The race was on to create the first controlled nuclear chain reaction. If American scientists couldn’t make this happen it would be impossible to construct a nuclear weapon of their own and the war could be lost.

Working in secret in an unused squash court underneath the stands of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field, scientists, students, and laborers worked day and night piling 50 and 100-pound bricks of graphite into a massive 771,000-pound egg-shaped reactor core. On the snowy afternoon of December 2, a few dozen people looked on nervously as cadmium rods were removed and the world’s first nuclear reactor was activated. Without any cooling or shielding system, it was possible that the world’s first fission reaction could also create the world’s first nuclear meltdown, right in the middle of the U of C campus. At 3:25pm the clicking of the Geiger counter confirmed that the experiment was a success, producing about enough energy to power a single light bulb. There were no cheers, toasts, or hearty slaps on the back. A bottle of chianti was passed for a few celebratory sips. Graduate student Leona Woods described the mood in the room saying, “There was a greater drama in the silence than if the words had been spoken.”

Later recognized as perhaps the greatest scientific experiment of the 20th century, team leader Enrico Fermi was heaped with praise. An Italian physicist who used his trip to Sweden to accept the Nobel Prize as an opportunity to escape Mussolini and defect to the United States, Fermi was called “the Pope” by his peers. Recognized as alternatively the “architect of the nuclear age” or the “architect of the atomic bomb,” few scientists from the modern era are held in higher regard. And it all happened right on the University of Chicago campus, where Milton Friedman would join the faculty just 5 years later in 1946.

There is a longtime cleavage in the academic community between hard science and social science, or what was once known as physics and metaphysics. What’s the difference? Metaphysics is defined as the study of abstract concepts like being and knowing – why are we here? Metaphysics is philosophy, the quest for eternal truth. Physicist Robert W. Wood was once asked to make a toast “To physics and metaphysics.” Wood described the physicist’s journey from its first burst of inspiration. The next step, he said, is consulting existing literature bolstering that idea. The physicist then carefully prepares experiments to test that idea to see if it can withstand scrutiny in a lab. Finally, the physicist’s idea turns out to be wrong, so this idea is rejected and our scientist moves on to something else. In the end, Wood diplomatically summed up the difference between physicist and metaphysicist saying that one has a laboratory and one does not.

Economics was not always considered a science. Back in the late 1700s when Adam Smith was writing, his area of study was known as “political philosophy.” Smith was continuing in the tradition of classical philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, who talked about some of the same basic ideas. At that time economics had not completed its metamorphosis from political philosophy to political economics to just plain economics. At that time economics was squarely in the metaphysical realm. However, embedded in Smith’s philosophical framework was the notion that society was a living organism. It was common then to see not just human beings as biological organisms, but culture as a kind of organism as well. In the time after Smith, political philosophers increasingly saw societies as having balance and equilibrium like the rest of nature. This belief in equilibrium is one of the chief articles of faith of the free-market religion. Classical economists like Smith and Neoclassical acolytes like Milton Friedman have zeroed in on certain shared similarities of human beings as a way to suggest that we are all motivated by the same essential laws of nature. It was in this way that economics began creeping from a social science, philosophy, to actual science.

The shift economics made from philosophy to science was slow. Tending carefully as the first green shoots of this new branch were forming was Alfred Marshall, called by some the founder of modern economics. Marshall made a conscious effort to break this area of study free from its philosophical roots and cultivate a new, value-free science. He believed it was possible to apply the scientific method and calculus to measure “marginal utility.” In economics utility is the benefit one gains from acquiring a product. Marginal utility is a way of conceptualizing that benefit into some kind of integer or measurable unit. (Science tends to pretend something doesn’t exist until some way is developed to measure it.) Once the proto-economists of Marshall’s era had a unit of measurement for economic theory it became possible for them to start making predictions seem more scientific and less philosophical.

This breakthrough led to what is known as the Marginalist Revolution. As political economics gave way to just plain economics, everybody who was anybody began adopting an air of objectivity and impartiality as they used charts and graphs and complex equations to measure and size up precisely how economic transactions work. At the time, the Marginalist method was once just one flavor among many taught and studied by aspiring economists, mixed right in there with Adam Smith and Karl Marx; “… it would be a long time before the uniformly mathematical approach we now associate with economics would establish dominance,” writes John Rapley. In the same way, early Marginalists came from a broad spectrum of political orientations. But eventually Free Market Capitalism and Marginalism joined together to establish a correct way for economics to be studied and understood.

Once the marginalists had developed a clean way of measuring economic theories it was time for them to start mapping out the economic laws of nature. At long last, their discipline could be as rigorous and mathematical as thermodynamics or chemistry. Demonstrating the laws of supply and demand would now be as self-evident as Newton’s law of universal gravitation. Mapping the law of scarcity would be as clear as when hydrocarbon reacts with oxygen to create combustion in a laboratory.

Next, let's take a closer look at how some of the old assumptions economists made back when they were philosophers undercuts their scientific claims. It's one of my favorite parts of this whole series.

This is part 6 of my series... be sure to check out parts ONE and TWO and THREE and FOUR and FIVE and subscribe so you can follow along.

Let us make them pay.

Share this post