Capitalism is threatened by collective power and tries to deflect blame by foisting the problems it causes onto the individual. This classic ad promoting environmentalism is a perfect example...

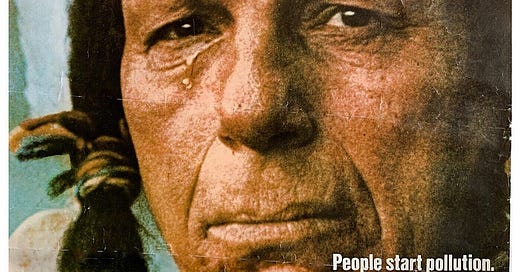

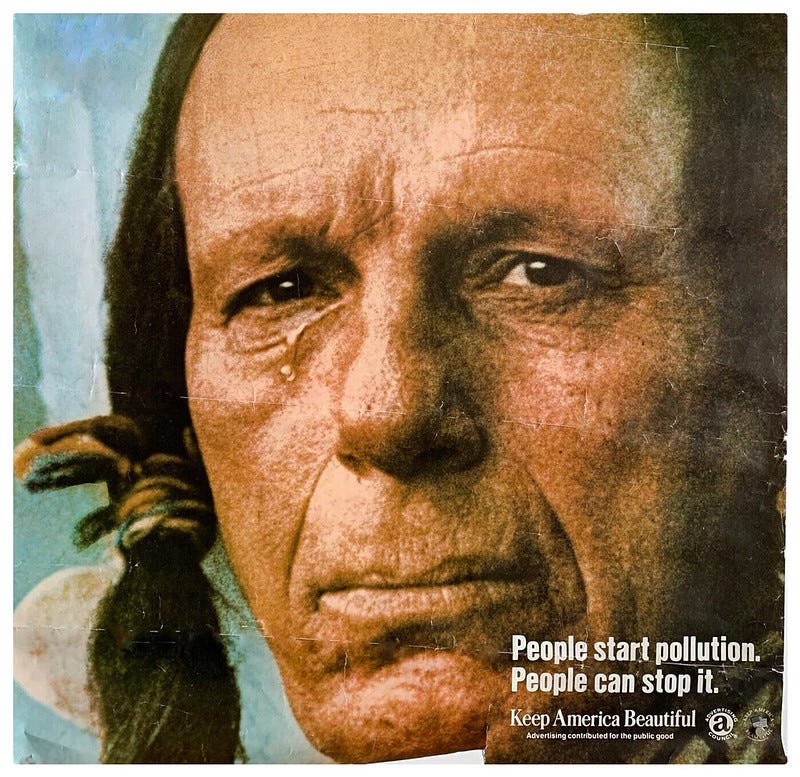

To the sounds of tribal drums, a proud Native American paddles his birch canoe down a stream. As the music builds, we see signs of modern despoliation floating on the water. Contrasting his fringed buckskin clothes, the camera pulls back to show this old-school Indian, right out of central casting, surrounded by modern factories billowing smoke. He pulls his canoe on to a shore covered with old tin cans and discarded boxes. As the narrator intones, “Some people have a deep, abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country,” a jagoff in a four-door sedan rolls down his window and tosses a full bag of fast food at the feet of our noble native (like, so full I ask myself, did he even eat any of that?!). As French fries and hamburger wrappers scatter around the man’s beaded moccasins, the camera pulls up and the narrator finishes his thought “… and some people don’t.” As we zoom in tight on actor Iron Eyes Cody’s profile, the narration continues. “People start pollution. People can stop it.” Cody turns his head to the camera, a single eagle feather protruding from his braids, as a single tear cuts a channel down his craggy cheek.

It’s one of the most famous and successful ad campaigns in history. My own father credited this spot for shaming many Americans into no longer dumping trash on the side of the road anymore. The ad won accolades and awards. Representatives for the Ad Council said that TV stations would request fresh copies of the spot throughout the 1970s because they wore out the original tapes from running them so many times. But all was not as it seemed.

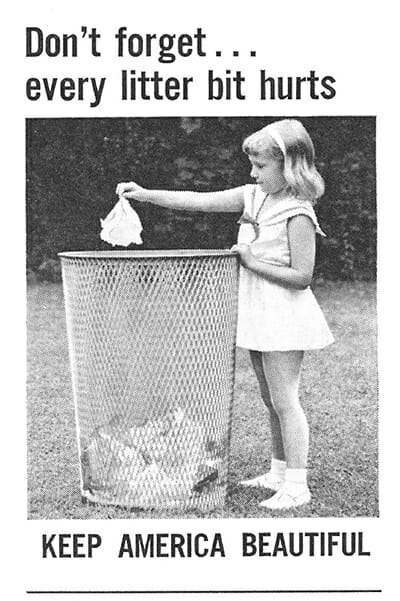

Leaving aside the fact that Iron Eyes Cody (birth name Espera di Corti) had about as much First Nations blood in him as Dean Martin or Jerry Lewis, this ad was about more than just littering. According to history professor Finis Dunaway, the Crying Indian campaign was a calculated effort by huge beverage and packaged goods corporations to deflect unwanted attention. Keep America Beautiful was a nonprofit created in the early 50s by the American Can Company and the Owens-Illinois Glass Company. Later on Coca Cola and Dixie Cup Company jumped aboard. Before the Crying Indian, little Susan Spotless used to prance around wagging her finger at litterbugs. But as Dunaway writes, “The shift from Keep America Beautiful’s bland admonishments about litter to the Crying Indian did not represent an embrace of ecological values but instead indicated industry’s fear of them.”

When the ad came out in 1970, the environmental movement was just gaining traction. Reusable milk, soda, and beer bottles had been the industry standard into the 1960s. The shift to throwaway products was partly responsible for the increase in litter that made the Crying Indian so sad. One of the primary complaints at the very first Earth Day was the solid waste crisis brought about by disposable containers. Those protests placed the blame for that crisis not on consumers but squarely on the shoulders of the beverage and packaging industry. Shortly after, old Iron Eyes Cody comes paddling downstream in a brilliant act of rhetorical jiu-jitsu. The propaganda campaign worked because nobody knew that Keep America Beautiful was an industry front. In a time when littering was much more common, the Crying Indian never seemed like a corporate shill designed to deflect attention away from powerful private players. He seemed so noble! The message that people start pollution and people can stop it didn’t seem insidious, it seemed conscientious. But, as Dunaway points out, “By making individual viewers feel guilty and responsible for the polluted environment, the ad deflected the question of responsibility away from corporations and placed it entirely in the realm of individual action, concealing the role of industry in polluting the landscape.”

This attitude carries all the way through to today’s emphasis on recycling. The truth is that sadly, recycling isn’t a huge net gain against environmental devastation. But this mentality that the consumers should be responsible and properly dispose of what industry gives us lives on. Of course, recycling is better for the environment than not recycling. But even better than all of us keeping aluminum cans and heavy-duty plastic laundry detergent bottles out of landfills would be trash that doesn’t take thousands of years to disintegrate. Better packaging options exist, but they are more expensive. And since industry always insists on the cheapest possible option, it becomes our responsibility to make sure that their packages don’t despoil our environment. This is backwards!

Recycling is an individualized solution to a society-wide problem. In the same way that Keep America Beautiful told us that it was our job to keep America beautiful, we are also told it is our individual job to deal with unemployment or poverty or outrageous healthcare costs. The reality is that these are political problems and they require concerted social effort to fix. We have reached the limits of what individual effort can achieve. We need collective action and collective power to address societal problems.

Business interests love it when they can foist their problems onto us. There is even a word for it: Externalities. An externality is any cost that a corporation can push off onto another individual or group. There are both positive and negative externalities. One positive example is public education. Both society and business benefit from having a well-educated workforce. The Industrial Revolution made business realize the value of educated workers, so public schools were established to help fill this need. Our tax money pays to educate children so that companies don’t have to waste resources teaching workers how to read and write. Our whole society benefits from having an educated population.

But there are negative externalities as well. Environmental destruction is the most common example. Toxic air, water, and soil are common byproducts of industrial manufacturing. Overfishing is a byproduct of industrial food production. But individual companies rarely pay for the negative effects that their industries wreak on our shared environment, using up natural resources as if they were both disposable and infinite. One 2013 UN study estimated global environmental externalities at $4.7 trillion a year – the economic costs of natural resource extraction, greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and healthcare costs due to air pollution. The same study estimated an even higher $7.3 trillion a year cost for externalities related to food production and oil extraction, costs that people like you and me foot the bill for so that business doesn’t have to. That second figure was the equivalent to 13 percent of global economic output for 2009.

Acceptance of the individualistic framework we saw in the Crying Indian ad is an example of how the power structure works in the United States. Business is the most powerful interest group in this country so they get what they want. What they want is for us to pick up the costs, the externalities, of doing business so they can maximize profits – which they get to keep. This amounts to socialism for them and capitalism for everyone else. Consider the 2008 financial crisis. Leading up to the crisis was a go-go feeding frenzy for the big banks and Wall Street. But when their gambling got out of control and the system threatened to collapse, it was up to the American taxpayer to bail them out. The banks got to keep the profits, but we got to pay the costs when things spun of control. The banks were made whole again by the US government, their creditors paid. But many average citizens lost their homes because those same banks had fraudulently sold loans to them.

Not even the fight to cure cancer is immune from this dynamic. As Michael Parenti describes in Power and the Powerless, billions are spent searching for a “cure” for cancer, despite the fact that most known cancer-causing agents are made by humans. Industrial pollutants, chemical additives, and emissions we regularly ingest in our air, water, and food cause cancer. We know this, it is not controversial. Just as we saw in the Crying Indian story, it would likely be easier from a scientific standpoint to remove the inputs that create the disease, rather than trying to fix what may not be fixable on the output side. Cancer need not be an individual struggle. We could work collectively to restrict the inputs that give people cancer. But as Parenti says, “… it is easier to spend billions looking for a cure than to challenge the big economic interests that are part of the cause. The tendency to define medical problems as separate from politico-economic power is itself a profound concession to politic-economic power.”

We have reached the limits of what rugged individualism can accomplish. Some problems require group solutions. If a city’s sewer system is failing, you don’t call one rugged individualist to fix it (Clint Eastwood rides into town on horseback squinting, a hand-rolled cigarette clenched in his teeth, a well-oiled six-gun strapped to his thigh, gripping his reins in one hand and a plunger in the other). Nor should problems like that be left up to individual homeowners to solve on their own. Big, collective problems require big, collective solutions. This is where politics and collective power come into play. We have collective power when we join together, it's time to use it.

Please also give a like, comment, restack, and share to help others find me here on Substack.

Let’s make them pay.

Share this post