Oh man, this series keeps on coming. I’ll just be clogging your inbox with these exceptional posts from last year and plenty of top-notch new content for the time being. I hope you don’t mind.

Free market capitalism is a false religion. In my previous post, I began telling the story of Lord John Meynard Keynes and his Keynesian reformation. Now, the story of how Free Market Fundamentalism took hold, and how communism helped bring it about.

Even at the absolute zenith of its influence, Keynesian economics never achieved the global dominance of Free Market Economics. Why is that? Because during the heyday of Keynesianism, there was a competing economic faith that was not part of the capitalist system. At that point, the world was still separated into First World, Second World, and Third World. As mentioned in an earlier post, the Second World was made up of the Soviet Union, Communist China, and smaller satellite nations like Cuba. These countries didn’t have anything to do with Keynesianism, because at its heart Keynesianism was still capitalism. The basic premise of the capitalist economy – who owns the factories and gets to make all the decisions about the profits – was left untouched by Keynesian policies. At its heart, Keynesianism was just a body cast designed to protect capitalism (giving it time to heal) and keep it from drying up and blowing away during the Great Depression. Lord Keynes wanted to preserve the capitalist system and he did. The rich were more than happy to put up with government intervention in the economy, regulations, and unions (Keynesian policies), in order to defend against encroaching Marxism.

And here we return to the cyclical nature of the Free Market religion. When the postwar boom times finally started to lose momentum in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Neoclassical and Neoliberal economists saw their chance. With the war in Vietnam and the first oil crises, inflation and stagflation, people started to question the Keynesian faith. This was Milton Friedman’s golden opportunity. Remember, Milton Friedman and Fredrich Hayek called themselves “neoliberals” who studied “neoclassical” economics. This is because they were harkening back to older schools of thought, discredited since the Great Depression. Friedman wanted to distinguish himself from the mushy, civil rights-loving liberals of his day by referring back to early liberal philosophers like Locke and Montesquieu. The “neo” liberals saw themselves as the new version of that.

Thanks for reading Let's Make Them Pay! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

The neoliberal, neoclassical resurgence was a reaction to the Keynesian philosophy that had become orthodoxy by the 1960s. One could foresee that at a certain point, Keynesian economic proscriptions would fail to provide the same oomph they once had. It was here that Milton Friedman’s patience paid off. As described in my series on Milton Friedman, he was just waiting for the right crisis to dust off his ideas and put them into practice. He was in the right place at the right time. It was two happy accidents of history that allowed this particular brand of economics to become a global phenomenon, unlike any world religion that came before.

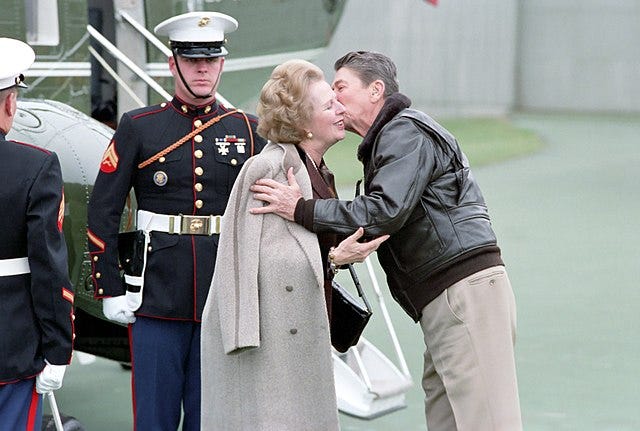

Friedman won influential adherents like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Reagan had this joke that the nine most terrifying words in the English language were “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” He and Friedman believed that the government should never interfere in the economy, that the government was always the problem. To them, freeing the market of all regulations and restrictions would bring peace and prosperity.

As discussed earlier, public benefit was never really the goal. Unleashing the market did cause stocks to surge, creating a massive upward distribution of wealth. In the same way that Keynesian policies won widespread influence in capitalist nations, Friedman’s brand of neoliberalism started in the US and UK and spread out from there. But the real quantum leap that separated Keynesian economics from Free Market Capitalism happened when the Second World suddenly evaporated. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, neoliberal policies – widely known as the “Washington consensus” – were quickly adopted in former communist states as they dumped their old economic model for go-go free market capitalism.

John Rapley makes an interesting comparison. Christian Millenarians believe that the time of Christ’s return is close at hand. They believe that spreading the Good Word is important because once all of humanity has been converted to their beliefs, the Second Coming will finally happen. Rapley points out that while Christian missionaries were never quite able to convert everyone, “here, suddenly, was another doctrine, which, under their noses, was getting ever closer to pulling off a very similar feat. Neoliberalism had become the state religion across most of the planet, and the holdouts were diminishing by the year.”

Next up, let's take a closer look at how economics bridged the gap from being considered "moral philosophy" to dismal science. It didn't happen overnight.

In the meantime, please like follow, favorite, and subscribe to my free Substack, where you can get more detail in every post.

This is part 5 of my series... be sure to check out parts ONE and TWO and THREE and FOUR and subscribe so you can follow along.

Let us make them pay.

Share this post