An innocent person would never plead guilty, right? Wrong.

In recent posts I have examined how capitalist production theories have infiltrated our legal system, turning the concept of American justice into a complete farce. Prosecutors have vast unchecked power to coerce defendants into accepting guilty pleas - which helps prop up their performance metrics but does little to ensure that our legal system punishes the guilty rather than the innocent.

An innocent person with no money is under incredible pressure to accept a prosecutor’s offer. If a person with no money is arrested that means they can’t make bail. A person who can’t afford to make bail will have to sit in jail until their court date which could be months or in some cases years into the future. In misdemeanor cases a prosecutor will frequently allow a person to walk out of jail almost immediately if they agree to take a guilty plea. For a person with no resources any significant time in jail waiting for trial can mean losing a job or even losing custody of their children. A lot of innocent people take the deal.

An innocent person will sometimes accept a guilty plea for more serious crimes as well. If a person is facing a rape or murder trial that could result in the death penalty, the decision to take the guilty plea can be a perfectly rational choice. Just imagine a prosecutor presenting a case where some sort of circumstantial evidence makes an innocent person doubt their chances for acquittal. After a grim cost-benefit analysis of the situation a slightly less awful guilty plea might sound better than risking the electric chair. Especially when expensive defense fees are also a consideration. If a prosecutor were to hold a gun to a suspect’s head and say “take this plea deal!” that would be considered coercion. However, when a prosecutor tells a suspect “if they don’t take this plea deal, I will seek the death penalty for this case,” that is not considered coercion. You and I may fail to see the distinction, but the American legal system depends on maintaining the pretense. Perhaps you think I am being unfair, but I would direct your attention to the Death Penalty Innocence Center’s list of more than 160 death row inmates exonerated since 1973. Innocent people do get executed in the United States.

Even setting aside the death penalty for a moment it is a fact that innocent people are being chewed up by our justice system. A 1970 Supreme Court case called North Carolina v. Alford allows defendants who don’t want to roll the dice on a trial to take a guilty plea while maintaining their innocence. This is an imperfect measure because not every person who makes an “Alford plea” is innocent and not every innocent person even knows that such a thing exists (also, not every judge accepts them and they are only available in 47 states and the District of Columbia). But just using one year as an example, in 1997 an estimated 65,150 state prison inmates (6 percent) and 2,472 federal prison inmates (3 percent) entered an Alford plea in their cases. If a mere one percent of that year’s Alford plea defendants were actually innocent (676 of 67,622) that’s more than were exonerated during the entire decade between 1990-1999 (399) according to the National Registry of Exonerations. The US Bureau of Justice Statistics said there were 2,220,300 adults incarcerated in US state, federal, and county prisons in 2017. There were an additional 4,751,400 on probation or parole. If a mere one percent of the 6,971,700 people in our justice system are innocent that’s almost 70,000, roughly the population size of a Chicago suburb like Cicero or Waukegan, Illinois. But the number of innocent people is likely a lot higher than one percent.

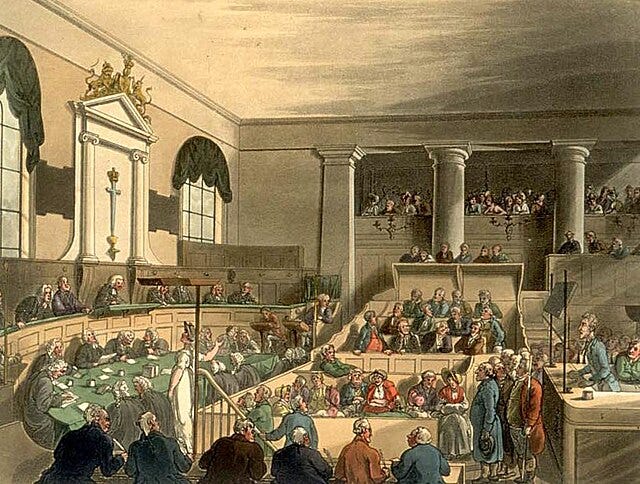

Before the Civil War plea bargains were basically unheard of. Part of the reason was that confessing guilt to a felony at that time would frequently be followed by execution. Another reason is that trials went quickly. The American colonies inherited their judicial system from the British, whose procedures at that time would seem very “wham bam thank you ma’am” compared to what we know from today’s Law and Order episodes. Yale law professor John H. Langbein describes how swiftly justice was administered up until the late 1700s at Old Bailey, the Crown’s central criminal court in London. Using only one or two juries the court could whip through twelve to twenty felony cases a day. Until 1794 no trial ever lasted more than a day. There was no legal counsel for either the defense or prosecution. There was no voir dire, questioning of potential jury members. There was no right against self-incrimination – so the accused was frequently the primary witness and source for testimony. There were basically no rules about presentation of evidence or cross-examining witnesses or abuse of police powers. Criminal appeals were basically nonexistent. It was a total free for all.

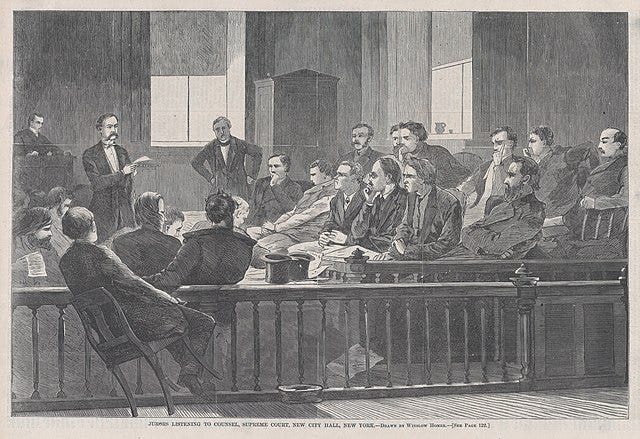

All of these things started to change in the early 19th century as modern legal proceedings began to take shape. But over time the reforms that made trials fairer also rendered them useless as a routine way of dealing with serious crime. Following the massive displacement and disruptions after the Civil War there was a surge in crime rates and American courts settled on plea bargaining as a way to clear cases quickly and ease an unsustainable burden on the justice system. Plea bargaining really caught on fast. For example, as Albert Alschuler writes, in New York city “… only 15% of all felony convictions in Manhattan and Brooklyn were by guilty plea in 1839, this figure increased steadily at decade intervals to 45, 70, 75, and 80. This last figure remained steady until 1919, when it grew to more than 85%. By 1926, 90% of all felony convictions in Manhattan and Brooklyn were by plea of guilty, and the figures for New York State as a whole revealed a comparable increase.”

Following the landmark Gideon v. Wainwright case, the Supreme Court said that even poor defendants were entitled to legal representation. Following the Miranda v. Arizona case, the Supreme Court said that police could no longer interrogate suspects without telling them that they had a 5th Amendment right not to incriminate themselves. Pretrial motions and modern legal discovery methods, or fact finding, also tend to slow the legal process to a crawl. On balance all of these developments are good. They protect the innocent and the weak. But they also create an environment where criminal jury trials take forever and can cost millions of dollars. It is for these reasons that 97 percent of federal convictions and 94 percent of state convictions result from guilty pleas.

The American legal system is completely overloaded. Public defenders are overwhelmed and underfunded – unable to cope with the demands imposed on them. Plea bargains are a way for them to keep relationships cordial and collegial with both prosecutors and judges. Judges are more than happy to avoid time-consuming trials if a defendant is willing to just take a guilty plea. Even some private defense attorneys can benefit from plea deals. Only a rich client can afford to drag a trial out and spend a fortune on billable hours. For the non-rich, “These attorneys collect their fees in advance, and once they have obtained their fees, their interests lie in disposing of their cases rapidly.” But it’s worth remembering that one of the main reasons the American criminal justice system is so overloaded is because the production demands of the drug war force police to keep cranking as many arrestees as possible into this overloaded system.

This is part 4 of a 5 part series on how capitalist production theories make a mockery of our justice system. In my next post we will try to find some historical context for where we stand.

Please give a like, comment, and restack this post so others can see it.

Let’s make them pay.

This is PART ONE of the series.

This is PART TWO of the series.

This is PART THREE of the series.

Share this post