Famous sociologist Abraham Maslow once said that "To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail." Well, when you're the biggest, most powerful capitalist nation on earth, you start to think capitalism can solve every problem you have.

I posted a series recently about how war planners tried to use capitalist production theory, also known as Technowar, to win the War in Vietnam. Please check that series out. Spoiler alert, it didn't work. Yet that didn't stop political leaders from trying the same failed strategies on the domestic front, which gave us the Technowar on Drugs.

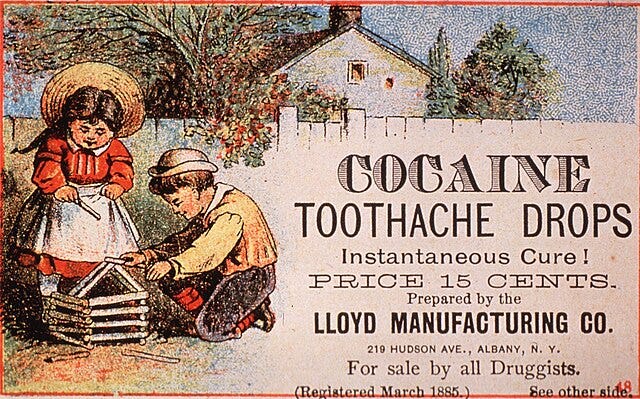

The War on Drugs got off to a slow start in the United States. Opiates, cocaine, and marijuana were all perfectly legal at one time. It’s said that physician Samuel Fuller probably brought some kind of opium/alcohol tincture to the New World aboard the Mayflower. Poppy extracts have been used in medicines for at least 5000 years since the time of the ancient Sumerians. Opiates were sold in over the counter products to treat everything from menstrual cramps to fussy children until the early 1900s. Early recipes for Coca-Cola (named for the coca plant, natch) called for about 9 milligrams of cocaine per glass until 1903 (compare that to your typical bump which contains about 20 to 50 mg). And as anyone who has seen Dazed and Confused remembers, some of the nation’s founders cultivated hemp plants as a common crop – though George Washington probably didn’t smoke up with Martha as one character described.

In 1906 Teddy Roosevelt passed the Pure Food and Drug Act which required that any “dangerous” or “addictive” substances be labelled. Over the next two decades a variety of state laws made it harder and harder to get opiates or cocaine legally. The Marijuana Tax Act effectively outlawed possession of pot in 1937. But even though these laws were on the books for decades there was no War on Drugs quite yet. In 1968 Lyndon Johnson created the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs which was merged into the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) five years later. Even so, local law enforcement was in no hurry to cooperate with any new federal agencies at first. Drugs were seen as street crime, a local matter. Federal agents going after drugs were seen as encroaching on local law enforcement’s turf. It was President Johnson who innovated a way around the problem of uncooperative local police: Bribe them! According to Radley Balko’s essential book Rise of the Warrior Cop, Johnson pioneered a new way of feeding money, equipment, and new law enforcement technology to local police through the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA). As Balko says “Johnson’s successors would quickly discover that introducing a funding spigot like LEAA, then threatening to pull it away, was an effective way to persuade local police agencies to adopt their preferred policies.”

The modern drug war began in earnest around 1970 with the passage of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. President Richard Nixon coined the term “War on Drugs” when promoting the new law, calling drug abuse “public enemy number one.” During the Reagan administration huge cash grants were doled out by the federal government to local agencies willing to prioritize drug investigations. A continuation from Lyndon Johnson’s era, the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 became the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program during George HW Bush’s administration. Named for a New York City police officer who was killed while protecting a drug witness, the program is a huge source of funding for the War on Drugs. Byrne funds have helped spread specialized narcotics task forces across the country. According to the Justice Department, drug task forces in some states are completely dependent on Byrne funds, getting as much as 90 percent of their budgets from them. As Michelle Alexander writes in The New Jim Crow, “it is questionable whether any specialized drug enforcement activity would exist in some states without the Byrne program.”

Here we have the most essential ingredient for the technowar on drugs. If we think of the War on Drugs as a production system there are debits and credits, just like in a factory. On the debit side we have crime: Possession of illicit narcotics, drug dealing, and drug-related crimes from petty property loss to violent assaults and murder. On the credit side we have drug and property seizures, arrests, and convictions. Drug arrests represent law enforcement’s equivalent to body counts in Vietnam. Major Neill Franklin retired after more than three decades with the Maryland State Police and Baltimore Police Department. He told Vox about his time as human resources chief at Baltimore PD. It was his job to oversee state and federal grants like the Byrne program:

“One of the requirements for completing a federal grant application for funds to combat drugs was showing how many drug arrests we made.The thinking was that the more drug arrests you have, the more significant your drug problem. If you have a significant drug problem, the federal government will give you more funds. So what did we do? We had our officers go out and make as many drug arrests as they could… Doing these evening and afternoon sweeps meant 20 to 30 arrests, and now you have some great numbers for your grant application.”

This presents a huge internal contradiction. It is law enforcement’s job to eradicate drugs yet at the same time they are dependent on the drug war to fund their operations. If American law enforcement were to somehow successfully eliminate all drugs in America, they would ensure mass layoffs and shrunken police budgets. Alexander refers to a drug task force in Oakland, California where the link was explicit: “The officers were under tremendous pressure from their commander to keep their arrest numbers up, and all of the officers were aware that their jobs depended on the renewal of a federal grant.” Police have a direct financial interest in demonstrating high production quotas for the perpetual continuation of the drug war. More than that, they have become completely dependent on drug warfare. As Alexander summarizes “The war has become institutionalized. It is no longer a special program or politicized project; it is simply the way things are done.” More drug arrests mean more money for police departments. Every police officer has a direct self-interest in making as many drug arrests as possible.

This is part 1 of a 5 part series on how capitalist production theories have infiltrated our criminal justice system, and why the drug war has always been doomed to fail. Please give a like, restack, and comment. If you really want to make sure you don't miss a post, please make sure to sign up for my Substack to have my posts sent directly to your inbox.

Let’s make them pay.

Share this post